Published online Aug 28, 2015. doi: 10.5319/wjo.v5.i3.82

Peer-review started: May 21, 2015

First decision: June 24, 2015

Revised: July 19, 2015

Accepted: August 13, 2015

Article in press: August 14, 2015

Published online: August 28, 2015

Thyroid lymphoma is an unusual pathology. Different subtypes of lymphoma can present as primary thyroid lymphoma. This review illustrates via imaging, findings and treatment the need for accurate diagnosis and timely treatment. Patients and methods: patient’s chart, pathological findings and radiological images were reviewed in a retrospective analysis. Over several days, this 80 years old woman developed airway obstruction and rapid enlargement of her thyroid secondary to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. She rapidly responded to her oncological protocol. Primary thyroid lymphoma is a rare disease. It is an important diagnosis to consider in patients presenting with rapidly enlarging neck masses. It is a treatable condition with fairly favorable overall survival even with the most aggressive histological subtypes.

Core tip: An elderly woman presented with an enlarging neck mass and airway obstruction requiring intubation. After imaging and histologic work-up, the final diagnosis of the neck mass was primary thyroid lymphoma (PTL). PTL is an important diagnosis to be considered in patients presenting with rapidly enlarging neck masses, usually demonstrating significant response to chemotherapy and favorable prognosis. Tissue biopsy rather than fine needle aspiration is the current gold standard for definitive histologic diagnosis, adding the benefit of subtyping, a crucial prognostic indicator. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is helpful for staging these lymphomas. The role of surgery in treating this entity has been diminished.

- Citation: Mehta K, Liu C, Raad RA, Mitnick R, Gu P, Myssiorek D. Thyroid lymphoma: A case report and literature review. World J Otorhinolaryngol 2015; 5(3): 82-89

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6247/full/v5/i3/82.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5319/wjo.v5.i3.82

Primary thyroid lymphoma (PTL) is a rare malignancy that has been estimated to constitute approximately 1%-5% of thyroid malignancies and 1%-2% of extranodal lymphomas[1-7]. Its annual incidence is reportedly similar to that of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, estimated as 2 per million per year[4,6]. A number of retrospective studies and case reports have demonstrated PTL more commonly affects women with reported mean age of incidence in the sixties[3-5,8].

Herein, we present an illustrative case of thyroid lymphoma, its evaluation, differential diagnosis, treatment and follow-up.

An 80-year-old Chinese woman was brought to the emergency department for shortness of breath. The patient presented to an outside hospital with shortness of breath of one week duration two months prior to presentation. At that time, physical examination and computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an enlarged thyroid gland as well as right neck lymphadenopathy. She developed severe respiratory distress on hospital day two, was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy of the right neck mass as well as the enlarged thyroid gland was reportedly “benign” demonstrating “large lymphocytic predominance and atypical lymphoid cells” possibly due to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, with “no phenotypic evidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma”.

Ten days after the initial biopsy, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy. The specimen was red-brown and spongy, contained two calcified nodules, and had scattered firm, yellow-gray areas comprising 40% of the gland. Pathology of the gland showed “lymphocytic thyroiditis and Hürthle cell adenoma with prominent areas of calcification and parathyroid parenchyma also present”. The pathology report attested that there was “no evidence of malignancy”.

After a complicated post-operative hospital course, with re-intubation due to respiratory distress, the patient was transferred to rehabilitation thirteen days following her surgery and was discharged in stable condition.

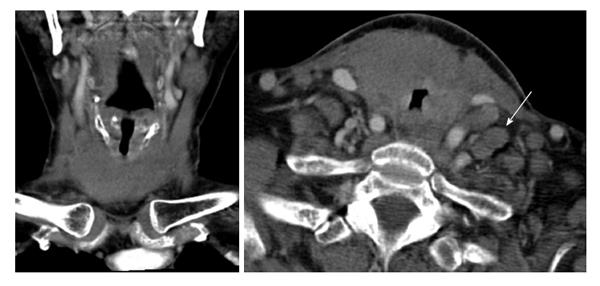

A few weeks following her discharge, she presented to our hospital with three days of worsening dyspnea and enlarging nodules in her neck. Despite stridor on arrival and multiple neck masses on exam, she had an oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. Neck CT scan revealed marked enlargement of the thyroid parenchyma with indistinct margins, mild laryngeal compression and soft tissue extension into the upper mediastinum to the left of the trachea. It also demonstrated extensive lymphadenopathy involving levels IA, IIA, IIB, V and the supraclavicular area (Figure 1).

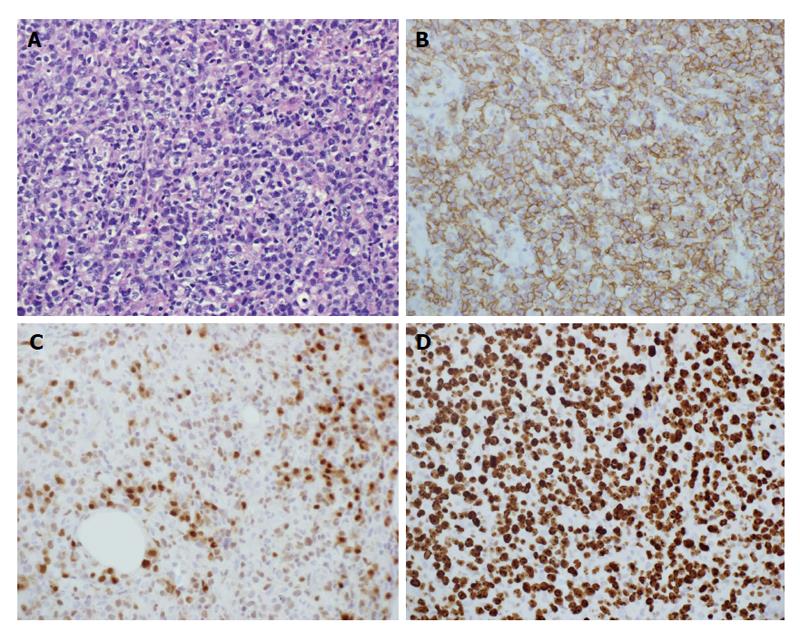

Airway compromise and CT findings demonstrating ragged involvement of the trachea prompted an emergent awake fiberoptic intubation and open left neck lymph node biopsy. The pathology revealed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, non-germinal center B-cell type. Immunohistochemical staining revealed the neoplastic cells being CD20 (+), CD10 (-), Bcl-2 (+), Bcl-6 (+), MUM1 (+), EBER (-), with a high proliferation index (Ki-67: 70%-80%), thought to indicate a more aggressive clinical course (Figure 2). Flow cytometry revealed a population of CD5 (-), CD10 (-), dim lambda light chain restricted large B-cells, most compatible with large B-cell lymphoma.

Staging included bone marrow biopsy, echocardiogram, and CT of the chest and abdomen. Flow cytometry, morphology and cytogenetic testing did not show evidence of marrow involvement. Chest CT demonstrated a soft tissue infiltrative mass measuring approximately 5.1 cm × 6.4 cm in the thyroid gland region, consistent with known B-cell lymphoma. Cycle one of R-CHOP chemotherapy (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone) was initiated.

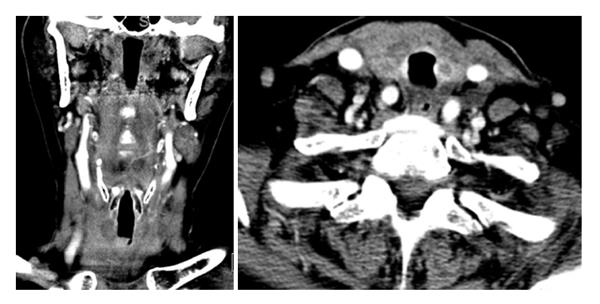

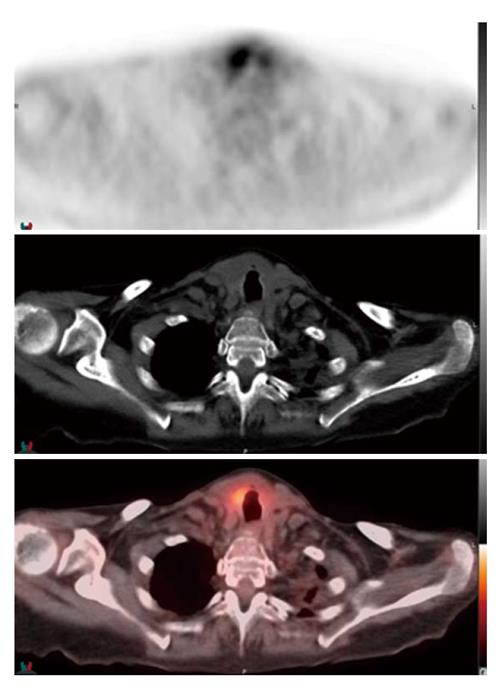

The patient was successfully extubated 48 h after initiating chemotherapy. Follow-up neck CT demonstrated marked decrease in the size of the thyroid gland with numerous left neck pathologic lymph nodes that remained prominent or mildly enlarged, however also decreased in size (Figure 3). The patient was discharged on day six of R-CHOP cycle one. The patient received additional cycles of R-CHOP as an outpatient, completing a total of six cycles. Staging whole-body 18-fluorine fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/CT scan confirmed stage II diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The scan demonstrated focal increased uptake in the region of the right thyroid gland, bilateral cervical lymph nodes, decreased in size and in number since the neck CT scan from one week prior, and minimally FDG avid residual uptake in the left supraclavicular zone and left subpectoral lymph nodes, also decreased in size (Figure 4).

Differential diagnosis for sudden growth of a thyroid mass includes spontaneous hemorrhage in a benign goiter, development of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma or thyroid lymphoma[9]. In one of the largest retrospective studies of PTL to date, Derringer et al[8] reported that all patients presented with a mass in the thyroid gland, which was noticeably enlarging in 72% of cases. Symptoms such as dyspnea, choking, coughing and hemoptysis, occurring secondary to compression or infiltration of neck organs by the mass, occurred in 31% of cases. Less commonly, classic B symptoms of fever, nights sweats and weight loss, also occur at presentation in approximately 10% of cases[6]. The duration of symptoms before diagnosis ranges from a few days to 36 mo, with a shorter duration in those with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[10].

As numerous retrospective studies have demonstrated, there is an association between chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, also known as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT), and the development of PTL. In a retrospective study of 171 patients diagnosed with PTL in Tokyo, Japan, authors report the incidence rate of PTL in HT patients as 16 persons per year per 10000 persons, significantly higher than the incidence of PTL in the Japanese general population[11]. Agrawal et al[1] report that circulating anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies have been found in 60%-80% of patients with PTL again further suggesting underlying lymphocytic thyroiditis as a predisposing factor for the development of PTL. Green et al[6] report that in patients with HT, the risk of PTL is at least 60 times higher than in patients without thyroiditis.

HT can be histologically seen in > 90% of cases of PTL. The pathogenesis of this relationship remains more or less obscure. It has been postulated that the relationship between these diseases is related to the presence of lymphocytes in HT, which provide the cells in which lymphoma may develop and to the chronic antigenic stimulation that is seen in HT, which predisposes malignant transformation of these lymphocytes[6]. In the effort of further clarifying the argument that PTL may evolve from HT, Moshynska et al[12] investigated a sequence similarity between HT and PTL: They reported clonal similarity in the IG heavy chain rearrangement sequences in the clonal bands of HT and PTL from the same patients, providing additional evidence that PTL may evolve from HT.

It is conceivable that the theory of antigenic stimulation explains the potential pathogenesis of PTL, especially given the potential parallel with gastric mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in which Helicobacter pylori provides the chronic antigenic stimulation[13]. Takakuwa et al[14] showed that aberrant somatic hypermutation which has previously been attributed to the development of proto-oncogenes in other types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), may play a role in the process of thyroid lymphogenesis in patients with HT, as well[5].

Head and neck irradiation is a known risk factor for the development of most thyroid cancers. It is unknown whether this predisposes patients to PTL. One study has suggested a potential link between EBV and the development of PTL[15]. HT is the only well known risk factor for the development of PTL.

Four main subtypes of PTL include extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of MALT, DLBCL without marginal zone lymphoma, DLBCL with marginal zone lymphoma (mixed) and follicular lymphoma (FL). Less common histological subtypes include Hodgkin lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma[8].

Not only is DLBCL the most common type of lymphoma worldwide, it is also the most common subtype of thyroid lymphoma, comprising 60%-85% cases of PTL[16]. Histologically, DLBCL of the thyroid consists of a relatively uniform population of large, abnormal lymphoid cells with lymphoepithelial foci and decreased or absent colloid and the presence of nuclear abnormalities[10]. DLBCL is typically positive for B-cell antigens, CD20 and CD19, and is often Bcl-6 positive, Approximately half of cases are Bcl-2 positive[5,10]. CD5, CD10 and CD23 are usually negative[5]. Evaluation of Bcl-6 and MUM1 expression can help further classify DLBCL into germinal center B-cell type (GCB) and non-GCB type. This is helpful in determining prognosis. DLBCL with CD10 (+) or CD10 (-)/Bcl-6 (+)/Mum1 (-) phenotype is classified as GC type, while CD10 (-)/Bcl-6 (+)/Mum1 (+) is classified as NGC type[17]. Positive cytoplasmic staining for nm23-H1 and non-GCB subgroup DLBCL is also associated with poorer prognosis[5,18].

The second most common subtype of PTL is MALT lymphoma. In contrast to DLBCL, patients are five times less likely to die with MALT compared to DLBCL PTL[5]. Histologically, MALT lymphoma of the thyroid is described as highly cellular with a prominent population of intermediate-sized lymphoid cells, lymphoepithelial lesions, reactive lymphoid follicles and a plasma-cell component. MALT thyroid lymphomas are typically positive for the B-cell phenotype.

The distinction of MALT thyroid lymphoma in the background of HT is a challenge when there is a predominance of small lymphoid cells. Although lymphoepithelial lesions are highly associated with MALT, they are not a specific finding[19]. Takano et al[20] described a novel method using vectorette polymerase chain reaction to distinguish MALT thyroid lymphoma from HT based on the monoclonality of the immunoglobulin heavy chain immunoreactive growth hormone gene, which was detected in 76.7% of lymphomas and conversely, not detected in 10 samples of tissue from patients with HT.

In addition to pure DLBCL, and pure MALT lymphoma of the thyroid, there are also cases with mixed presentation of DLBCL and MALT features. The mixed histological subtype accounts for approximately one-third of cases of PTL[10].

The fourth major subtype, follicular lymphoma (FL), accounts for approximately 10% or less of PTL cases. Histologically, FL usually demonstrates a typically follicular lymphoma morphology, with neoplastic nodules of mixed centrocytes and centroblasts[12]. FL can be distinguished from MALT by positive staining for CD10 and Bcl-6, the presence of typical follicular architecture and the lack of immunoglobulin heavy chain expression[5].

In FL, Bcl-2 positive staining is associated with disseminated disease, whereas Bcl-2 negative staining is more likely to be localized.

Prognostically, when stratified by histologic subtype, the 5-year disease specific survival of DLBCL is 75%. MALT responds very well to treatment and has a 5-year disease specific survival of > 95%, and FL falls in between the two with a 5-year disease specific survival of 87%[4]. Not only is the accurate identification of PTL subtype by histology very important for prognostic reasons, more importantly, therapeutic intervention largely depends on histologic subtype as well as stage; therefore, accurate histologic diagnosis is critical.

Since the introduction of FNA for the assessment of thyroid masses in the 1980s, FNA has been established as one of the first diagnostic procedures performed for patients with a thyroid mass or nodule and did allow the diagnosis of PTL to be made without surgical intervention in many cases. However, the role in PTL is questionable and the accuracy of FNA for PTL has been reported to range from 25% to 90%[3]. False-negative results may be caused by sampling error as HT may coexist with MALT[21].

Furthermore, when FNA is combined with flow cytometry, it can give a complete diagnosis in 82% of cases. Nonetheless, tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for histological diagnosis[16], especially in distinguishing thyroiditis from MALT lymphoma and in ensuring that aggressive histologies are not missed, especially in mixed histology disease[10]. When FNA suggests but does not confirm PTL, open biopsy is suggested for further histological confirmation[15,22].

Imaging studies may play a potential role in diagnostic and pretreatment evaluation. Ultrasound has long been the standard imaging modality for thyroid pathology, but its utility in PTL is debated. Ultrasonographic patterns of PTL have been classified into three types; nodular, diffuse and mixed[23]. Posterior acoustic enhancement, or posterior echoes, are characteristic of all three types and can help distinguish lymphoma from other thyroid pathology[10,23,24]. The nodular type is characteristically limited to one lobe, with a defined separation between lymphomatous and non-lymphomatous tissue, and hypoechoic, homogeneous and pseudocystic internal echoes[10,23]. In comparison, the diffuse type demonstrates enlargement of both lobes, with hypoechoic internal echoes and indistinct borders between lymphomatous and non-lymphomatous tissue[10,23]. In a prospective study of 165 patients with suspected PTL based on ultrasound, 47.9% were pathologically confirmed. The positive predictive value of ultrasound was higher for the nodular type (64.9%) and the mixed type (63.2%) than for the diffuse type (33.7%), possibly secondary to resemblance of the diffuse type to thyroiditis[10]. Though the individual utility of these ultrasonographic findings is limited, when used for guidance purposes with FNA or core needle biopsy, ultrasound may play a more important role in PTL.

As patients with PTL may present with rapidly enlarging masses and symptoms of compression, CT scan is often obtained in the emergency room. Previous reports of imaging characteristics of PTL as outlined by Kim et al[24] suggest PTL appears as a homogeneously enhancing mass without invasion of the surrounding structures on CT scan; however, two cases they described demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement compared to surrounding muscles without calcification or hemorrhage. Klyachkin et al[25] reported that imaging studies were of little help in diagnosing PTL and that CT scan cannot differentiate non-Hodgkin’s thyroid lymphoma from other thyroid tumors. Nonetheless, CT scan remains important for staging as well as for the assessment of airway compromise.

Over the past thirty years, the treatment paradigm for PTL has shifted. Although previously managed surgically, PTL treatment has evolved with the introduction of effective chemotherapeutic regimens. Treatment of PTL is now dependent on histological subtype. In a retrospective study analyzing patterns of care over the last two decades, Cha et al[3] found that before 2006, the mainstay of treatment was surgery and 8 of 10 patients with high grade lymphoma (DLBCL, Mixed, Burkitt) were treated with thyroidectomy followed by adjuvant treatment, while after 2006, only 1 of 11 patients received surgery and the rest were diagnosed by biopsy with subsequent chemotherapy. In a study of 1408 patients with PTL over 32 years, similar declines in the use of surgery were noted. Eighty-one percent of patients were surgically treated between 1983-1987 and only 61% were surgically treated between 1997-2005[4].

Though surgery still plays a role in diagnosis, and possibly in early stage locoregional treatment of more indolent disease as well as in palliative treatment for compressive symptoms, chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. Current treatment recommendations for PTL are histology specific. MALT lymphoma is a more indolent disease, and some have proposed that it can be treated with single modality, locoregional therapy (surgery/radiotherapy). Thieblemont et al[26] found that overall and disease free survival at five years of 100% in five patients with stage IE or IIE MALT PTL treated with thyroidectomy alone. Surgery and radiation were associated with improved disease specific survival for early stage dis–ease, and a study of 62 patients from Mayo clinic found thyroidectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy provided long-term cure for PTL contained within the capsule[4]. Meanwhile, Klyachkin et al[25] attest that the role of surgery for stage IE and IIE is still debated and survival rates do not seem to be improved when radical surgery is added to the treatment regimen.

Localized therapy such as surgery or radiotherapy may be an option for indolent disease such as MALT or FL. DLBCL is typically a more aggressive form of PTL and chemotherapy is required. CHOP is the most commonly used treatment regimen. Rituximab, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2006, is a monoclonal B-cell antibody that selectively binds to CD20 antigen on pre-B and mature B-lymphocytes[5]. In a trial of 197 patients, Coiffier et al[27] compared outcomes with CHOP alone and CHOP plus rituximab therapy, finding significant benefit of R-CHOP compared to CHOP alone in the treatment of both patients with low risk disease and those with high-risk disease.

In addition to the combination of CHOP and rituximab, combined modality treatment with chemotherapy and radiation has also been considered in the literature. In a review of 12 reported studies of a total of 211 patients, Doria et al[28] found a benefit of combined chemoradiation therapy with significantly lower relapse rates. In another study of 51 patients with stage IE or IIE thyroid lymphoma, the 5-year failure-free survival by treatment was 76% for surgery/radiation, 50% for chemotherapy alone and 91% for combined multimodality treatment[7].

Although PTL is a rare disease, it is an important diagnosis to consider in patients presenting with rapidly enlarging neck masses. It is a treatable condition with fairly favorable overall survival even in with the most aggressive histological subtype.

In conclusion, this case supports the literature in regard to epidemiology, presentation and other characteristics of PTL. Additionally, it raises questions regarding efficacy of FNA, the possibility of sampling error and the potential for human error in pathologic tissue examination. If our patient had pathologic evidence of DLBCL at her initial presentation, the case also demonstrates the futility of surgical intervention with thyroidectomy given the rapid recurrence of symptoms in the absence of systemic intervention. Though the rarity of PTL precludes clinical trials of treatment regimens, it appears that data extrapolated from retrospective studies and other extranodal lymphomas has great value in the treatment of PTL. Based on FNA, if PTL is suspected, it is suggested that definitive pathology be obtained, which can be accomplished by core biopsy or open biopsy. Once the diagnosis is established, the treatment of PTL is similar to systemic lymphoma treatment.

A 80-year-old woman with a rapidly enlarging neck mass and airway compromise.

The patient had a primary non Hodgkin B-cell thyroid lymphoma.

The differential diagnosis for sudden and rapid growth of a thyroid mass includes spontaneous hemorrhage into a benign goiter, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma and thyroid lymphoma.

Flow cytometry performed on the left lymph node sample revealed a population of CD5 (-), CD10 (-), dim lambda light chain restricted large B-cells, most compatible with large B-cell lymphoma.

Neck computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a large infiltrative thyroid mass with associated airway compromise and extensive bilateral cervical/supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, however neck CT and 18-fluorine fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT one week following resection demonstrated decreasing size and number of the lymph nodes.

Fine needle aspiration and subsequent left neck lymph node biopsy revealed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, non-germinal center B-cell type.

Patients with an IPI greater than 1 should be managed with six courses of R-CHOP, and these results can be applied to primary thyroid lymphoma.

All terms used in this manuscript are standard medical/pathological nomenclature.

This case demonstrates the aggressive nature of primary thyroid lymphoma and how to arrive at a diagnosis in patients with rapidly evolving thyroid masses. It denotes the possible pitfalls of histologic analysis, the futility of surgical intervention and the effectiveness of chemotherapy in treating this disease.

This manuscript is a rare case report and literature review, which is significant to guide clinicians both to raise awareness of this kind of disease and to standardize its diagnosis and treatment.

P- Reviewer: Kan LX, Zhang Q S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Agarwaf N, Wangnoo SK, Sidiqqi A, Gupt M. Primary thyroid lymphoma: a series of two cases and review of literature. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:496-498. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Alzouebi M, Goepel JR, Horsman JM, Hancock BW. Primary thyroid lymphoma: the 40 year experience of a UK lymphoma treatment centre. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:2075-2080. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Cha H, Kim JW, Suh CO, Kim JS, Cheong JW, Lee J, Keum KC, Lee CG, Cho J. Patterns of care and treatment outcomes for primary thyroid lymphoma: a single institution study. Radiat Oncol J. 2013;31:177-184. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Graff-Baker A, Roman SA, Thomas DC, Udelsman R, Sosa JA. Prognosis of primary thyroid lymphoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1,408 cases. Surgery. 2009;146:1105-1115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Graff-Baker A, Sosa JA, Roman SA. Primary thyroid lymphoma: a review of recent developments in diagnosis and histology-driven treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:17-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Green LD, Mack L, Pasieka JL. Anaplastic thyroid cancer and primary thyroid lymphoma: a review of these rare thyroid malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:725-736. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mack LA, Pasieka JL. An evidence-based approach to the treatment of thyroid lymphoma. World J Surg. 2007;31:978-986. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, Bijwaard KE, Heffess CS, Abbondanzo SL. Malignant lymphoma of the thyroid gland: a clinicopathologic study of 108 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:623-639. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 225] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Eng OS, Lesniak S, Davidov T, Trooskin SZ. Diagnosing thyroid lymphoma: steroid administration may result in rapid improvement of dyspnea : a report of two cases. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:e11463. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stein SA, Wartofsky L. Primary thyroid lymphoma: a clinical review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3131-3138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Watanabe N, Noh JY, Narimatsu H, Takeuchi K, Yamaguchi T, Kameyama K, Kobayashi K, Kami M, Kubo A, Kunii Y. Clinicopathological features of 171 cases of primary thyroid lymphoma: a long-term study involving 24553 patients with Hashimoto’s disease. Br J Haematol. 2011;153:236-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moshynska OV, Saxena A. Clonal relationship between Hashimoto thyroiditis and thyroid lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:438-444. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ansell SM, Grant CS, Habermann TM. Primary thyroid lymphoma. Semin Oncol. 1999;26:316-323. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Takakuwa T, Miyauchi A, Aozasa K. Aberrant somatic hypermutations in thyroid lymphomas. Leuk Res. 2009;33:649-654. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Matsuzuka F, Miyauchi A, Katayama S, Narabayashi I, Ikeda H, Kuma K, Sugawara M. Clinical aspects of primary thyroid lymphoma: diagnosis and treatment based on our experience of 119 cases. Thyroid. 1993;3:93-99. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Katna R, Shet T, Sengar M, Menon H, Laskar S, Prabhash K, D’Cruz A, Nair R. Clinicopathologic study and outcome analysis of thyroid lymphomas: experience from a tertiary cancer center. Head Neck. 2013;35:165-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Müller-Hermelink HK, Campo E, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275-282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2826] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2945] [Article Influence: 140.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Niitsu N, Okamoto M, Nakamura N, Nakamine H, Bessho M, Hirano M. Clinicopathologic correlations of stage IE/IIE primary thyroid diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1203-1208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morgen EK, Geddie W, Boerner S, Bailey D, Santos Gda C. The role of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of thyroid lymphoma: a retrospective study of nine cases and review of published series. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:129-133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Takano T, Miyauchi A, Matsuzuka F, Yoshida H, Notomi T, Kuma K, Amino N. Detection of monoclonality of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene in thyroid malignant lymphoma by vectorette polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:720-723. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sangalli G, Serio G, Zampatti C, Lomuscio G, Colombo L. Fine needle aspiration cytology of primary lymphoma of the thyroid: a report of 17 cases. Cytopathology. 2001;12:257-263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Meyer-Rochow GY, Sywak MS, Reeve TS, Delbridge LW, Sidhu SB. Surgical trends in the management of thyroid lymphoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:576-580. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nam M, Shin JH, Han BK, Ko EY, Ko ES, Hahn SY, Chung JH, Oh YL. Thyroid lymphoma: correlation of radiologic and pathologic features. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:589-594. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Kim EH, Kim JY, Kim TJ. Aggressive primary thyroid lymphoma: imaging features of two elderly patients. Ultrasonography. 2014;33:298-302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Klyachkin ML, Schwartz RW, Cibull M, Munn RK, Regine WF, Kenady DE, McGrath PC, Sloan DA. Thyroid lymphoma: is there a role for surgery? Am Surg. 1998;64:234-238. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Thieblemont C, Mayer A, Dumontet C, Barbier Y, Callet-Bauchu E, Felman P, Berger F, Ducottet X, Martin C, Salles G. Primary thyroid lymphoma is a heterogeneous disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:105-111. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235-242. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3975] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3845] [Article Influence: 174.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |